There have been many great moments since I started The Mill during the first lockdown just over nine months ago, but the very best came last Friday when I offered Dani a job as our first staff member. She joins as a full-time reporter and photographer this month, having just graduated from her journalism course. It’s her first job in journalism and her first job in Manchester, and I’m sure many of you who have enjoyed her writing and photos in the past six months will be pleased to hear this news (if you want to congratulate her or leak her some sensitive emails, she’s dani@manchestermill.co.uk).

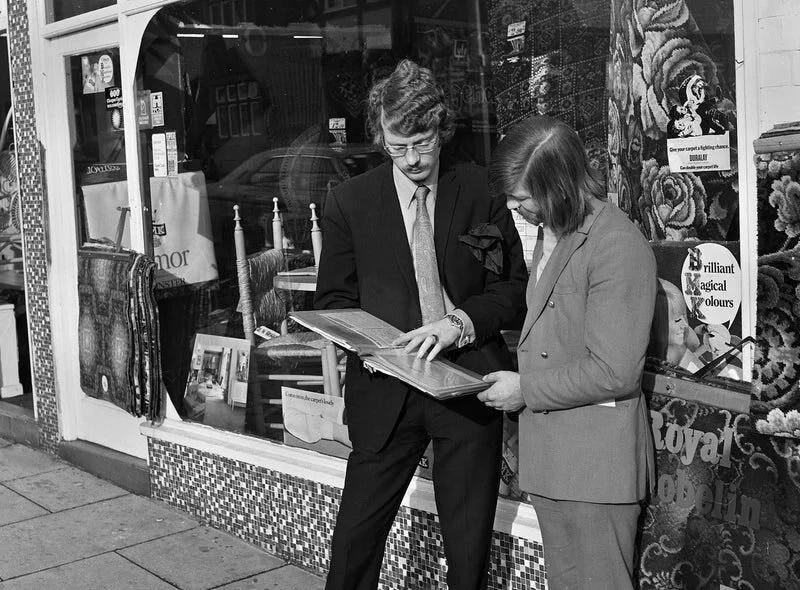

Dani first got in touch with me last September, asking to do her course placement with The Mill. “I understand that The Mill is only a few months old and you have no office, but in these present circumstances that isn’t an issue,” she emailed. We actually did have an office — a greasy spoon called the Metro Cafe next to Chorlton metro station where I used to spend my mornings drinking a series of large cappuccinos and where we had our first “editorial conferences” to plan our coverage.

The new intern’s first story was about the “ginnel gardens” of Levenshulme — a beautifully narrated portrait of local people breathing life into un-used spaces in their local community.

“A walk down Levenshulme high-street offers up a colourful array of mini-marts, betting shops and discount stores with leaflets posted over the windows. A chicken shop is fronted by an impossibly large pane of clear glass, its signage a fluorescent green. The inside resembles an arcade – a blaze of white lights and TV screens - rather than an eatery.

A little further along, a square of empty land has been left to rewild itself behind a billboard and spiked fence. Styrofoam takeaway boxes, crushed plastic cups and shreds of carrier bags are scattered amidst tall grass and blackberry thickets. It’s mid-September and they are starting to ripen. Nobody pays much notice to the litter.”

I knew from reading her first draft that this was the kind of journalism I wanted to publish — reporting that takes readers on a journey and manages to convey not just information but also a sense of wonder and delight. It’s why Dani has been such an asset to The Mill ever since, and why I’m so excited she’s joining us full time. So that’s the good news…

A warning from Martin Lewis

Recently I was invited to speak to the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Media, a committee of MPs and Lords who spend their time thinking about the health of the media industry. It was a good chance to bring The Mill to a wider audience and the topic for the panel was “How has the pandemic highlighted the importance of local media and how can it endure?” I thought it was worth addressing that question in a newsletter too.

The title for the discussion chosen by the MPs is accurate — the pandemic certainly has highlighted the importance of local news. For fairly obvious reasons. When there’s a deadly virus spreading through your neighbourhood, local information is what matters. Local news websites have reported massive spikes in traffic as people seek out the information that might keep them alive or allow them to interpret the local rules. And lots of local reporters have done a fantastic job of serving that need.

But sadly, Covid-19 is not going to save local journalism. It will not arrest the long-term decline of local newspapers, which have been shedding jobs in eye-watering numbers since about 2001. It won’t even stanch the bleeding. There was a sense among some of the panellists and politicians asking questions that this might happen, but I’m afraid they will be disappointed.

Why? Because the problem in local news isn’t fundamentally about how interested people are in local stories. People have always have been interested in local stories, and they always will be. The place we live is really important to us and our identity. Stories about our streets and our history and the people who run our schools and theatres have tremendous salience to us.

What I’m saying is: Yes, the pandemic has boosted interest in local information, but that interest was already very high! The issue has not been about a lack of appetite for the delicious meal that is local journalism, it’s been about how you pay for that meal to be put on the table. And how you make sure that the meal is nutritious and locally-sourced rather than mass-produced and covered in off-putting sauces that ruin the experience of eating it (ads…).

Before the metaphor police arrest me for a breach of the peace, I’ll just say: The problem in local news is the business model. As we have written about before (here and here), online advertising has not proved anywhere near as lucrative as local print advertising used to be for newspapers. And since almost every company in the industry picked online ads as its primary business model in the digital age, we have seen precipitous, calamitous declines in revenue across the entire industry.

One consequence of this is well known: local newspapers cut costs to the point that they are now trying to cover the same areas with skeleton staffs. Town newspapers in Greater Manchester that used to have 30 or 40 journalists onboard can now count their editorial teams on one or two hands.

Another consequence was that a bizarre game of online traffic-hacking game began. Newspapers needed to hit ungodly traffic targets to make the kind of money from online ads that would sustain even a skeleton newsroom, and that meant pumping out stories that ‘do well online’ regardless of who the readers are. Very quickly, many local newspapers sites were publishing lots of stories about TV gaffes and celebrities’ social media posts that have nothing to do with their local area.

If a particular format works well, the big media groups who own 80% of local newspapers will replicate it endlessly across their sites. That’s why you will very often see headlines about Money Saving Expert founder Martin Lewis warning us about something — we just have to click on the story to find out what.

Interestingly, Martin Lewis himself isn’t a fan of the blanket coverage these local sites are giving him. He recognises the stories for that they are — cynical attempts to game traffic out of the trust he has built up in his name. Or as he puts it: “They’re newspapers writing up my TV appearances rather than paying journalists to do journalism.” I’m told Lewis complained to Reach Plc — the company that owns the Daily Mirror, Manchester Evening News and dozens of local newspapers — about the stories recently.

Often these non-local traffic-hacking posts are the most-read stories on local newspaper sites. Many of them are written specifically to perform well on Google, so that if anyone in the country (or world) is searching out information about a topic, they will land on this story, regardless of where they live.

A few days before I spoke to the parliamentary group, I was browsing the Birmingham Mail (also owned by Reach Plc) and the top five most-read stories that day were all about the launch of the PlayStation 5. None of the stories had any local link whatsoever. Someone whose job it is to drive traffic to that website had worked out you could get millions of clicks from Google by covering this topic, and was doubling down hard.

Fair enough, that’s their job. Don’t blame the journalist. To reprise a phrase beloved of undergraduate Marxists: it’s much more structural than that. The reason these stories are taking over local newspaper sites is that the underlying business model — online ads — incentivises editors to produce them.

Young journalists are not choosing to write so many stories in a day that they can’t speak to a single source on the phone or go out and do a single interview. The reporter who wrote a couple of those PlayStation 5 stories published 45 posts in one day. It’s difficult to do any meaningful journalism if you are writing three or four stories in a day, let along 10, or 20 or 45.

The real renaissance

There is no way out of this malaise that does not involve large numbers of people paying for local news. The news organisations that have adapted most successfully to the digital age and been able to invest in quality journalism rather than cutting it back have business models that are led by reader subscriptions: publishers like The New York Times, the FT and The Economist.

Online ads can supplement the revenues of great media companies, but they can’t be the primary business model. Why? Because they incentivise the wrong thing — reach rather than quality. They generate so little income per reader that newspapers have to go hunting for millions of readers rather than serving a small number well. Which is literally the antithesis of what local news is supposed to do.

Subscriptions on the other hand align the incentives of readers (getting good-quality local reporting) with the incentives of media companies (growing their revenues). If your main funding is coming from your readers, your main priority is to serve them with good quality, well-researched, locally-relevant stories. If a subscription-based local media company starts pumping out stories about what Phillip Schofield said on TV this morning, readers will unsubscribe and it will make less money not more.

And this model can work. The Mill shows that. We turned on our subscriptions less than six months ago and we already have enough paying members to break important stories, commission an excellent team of contributors, and hire Dani. Last week we passed 800 paying members — imagine what we will be able to do in the years ahead when we have thousands of them.

This is the real renaissance in local journalism that we need — one that is driven by establishing a new business model for news that has the right incentives built-in. And it won’t just be The Mill doing it. In the past few months, I’ve had at least five calls with people who are trying similar models in towns around the country, and this week I’m doing a Zoom with two great journalists who are doing it in Ireland. I also regularly chat to Tony Mecia, my new friend who runs a subscription-based newsletter doing quality journalism in Charlotte, North Carolina and who has been a great source of advice.

Something exciting is afoot and by the end of the year, I think we will be able to discern a new local media ecosystem emerging from the wreckage of the old one.

A Mill newsroom

And now the second bit of exciting news for the Millers with the patience to make it to the end. We have just signed a lease to take a tiny office space just off St Ann’s Square. So The Mill will have its first newsroom, with enough space for us: me, Dani, our new trainees, and our freelance contributors to come in when they are working on a story.

It will also allow Millers to come in and speak to us in person. We will have a time each week where members can arrange to pop in and talk to us about a project they are working on or explain an issue in their neighbourhood that they want us to investigate.

In the town near where I grew up, both local newspapers used to have their offices on the high street so people could pop in while doing their shopping and pass on a story. It helped to ensure the papers stayed connected with their readers. Those offices have long shut, as they have across the country, and not just in small towns. On Friday it was announced that newspaper offices were being closed down in 15 places, including Cambridge, Derby, Huddersfield, Leicester and Stoke-on-Trent.

Once Mill HQ is open for business and the rules allow it, we will invite you in. Until then, thanks for your support in growing this venture. If you’re on the fence about joining as a member, please do get on board. We need everyone we can get. All hands to the pump.

To adapt a Chinese proverb, the best time to fix local news was 20 years ago. The second best time is now.

Joshi Herrmann, Founder & Editor of the Manchester Mill